Why are Montessori schools bad? Depending on who you ask you're likely to get a variety of answers. You're sure to get an earful from former Montessori moms, while former students (and teachers!) will have their own opinions. Even folks who have never set foot in a Montessori school love to expound on the criticisms they have heard in passing.

Personal opinions (or in some cases vendettas) are not facts. For every horror story concerning Montessori education, there is also a success story. And so it goes with methods of teaching that veer from the mainstream.

Keep reading to learn more about Montessori's methods and why some people are critical of them.

What is Montessori?

Montessori is an unconventional method of early childhood education that was conceived by an Italian physician named Maria Montessori in the early 20th century, circa 1906.

©Boris15/Shutterstock.com

To more fully understand the current criticisms, it helps to have a working knowledge of Montessori's philosophy, which is broken down into five principles:

- Respect for the whole child

- Acceptance of the child as a sentient being with an absorbent mind

- Awareness of sensitive periods when the child's mind is ready to acquire new skills

- Access to a prepared environment in which the tools of learning are organized and waiting

- The child is a capable teacher, able to educate him/her/themselves, aka auto-education

Applying these principles in the classroom nurtures independence and fosters creativity.

In a perfect world.

Unfortunately, we do not live in a perfect world. Real life in the 21st century affects us and our kids in ways that Maria Montessori could have never imagined back at the dawn of the 20th century when she took her first class of Montessori students. The majority of her first class had learning differences or were poverty-stricken, issues that may not afflict many modern families considering this education style.

The initial success of Montessori's method led to its rapid spread across Europe; her methodology made its way to the shores of North America in 1912. Out of approximately 15,000 Montessori schools scattered across the globe today, about 20 percent of them are located in the United States.

That there continues to be widespread interest in, acceptance of, and adherence to Montessori's methods over a century after they were introduced speaks to their viability. So, what's not to like? Are Montessori schools bad?

Criticisms of Montessori Education

Accessibility

One of the more valid criticisms of Montessori education lies in its accessibility – or lack thereof.

Of the 3,000 Montessori schools in the U.S., around 600 (20 percent) are publically funded. That sounds pretty reasonable until you realize that 80 percent of the Montessori schools in the U.S. are private. And private Montessori schools come with fancy price tags.

Yearly tuition for private Montessori preschools averages $15,000 nationally. However, it's easily more – much more – in metropolitan areas.

Tuition at The Metropolitan Montessori School located in the Yorkville neighborhood on Manhattan‘s Upper West Side is $29,000 on the low end (preschool 1/2 days), and $59,000 for the grade school. These rates are comparable to those at The Montessori Schools, located in the Flatiron and Soho neighborhoods of Manhattan, where full-day preschool tuition is just shy of $40,000 a year.

©szefei/Shutterstock.com

Jet across the country to California, and it's a little more reasonable. Little Paws Montessori School located in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles offers toddlers five full days (8:30 a.m.-3 p.m.) for $22,000.

Figures like these lend credence to the idea that Montessori schools aren't particularly accessible. Having a public option creates a bit more accessibility, though Montessori remains out of reach for the average American family.

Lack of Structure

Another complaint that is echoed among former Montessori adherents is the lack of structure in the Montessori classroom. Maria Montessori built her model around the idea that children will gravitate to the activities that interest them. How that translates in a classroom of 28-35 (Montessori's own numbers) students of various ages is another matter altogether. Theory vs. Practice.

In theory, children do have the tendency to gravitate to tasks that seem interesting to them.

In practice, in a classroom in which the teacher acts as a gentle guide and observer rather than a director or disciplinarian, this lack of structure can prove to be disruptive, if not downright chaotic.

©haireena/Shutterstock.com

However, experiential, self-guided learning is the cornerstone of Montessori's pedagogy, and while this approach to learning is well-suited to many children, others find it intimidating.

To be sure, Montessori classrooms are, at times, busy, noisy beehives of activity. Many children, particularly those with sensory issues, learning differences, and/or autism diagnoses, can feel overwhelmed in classrooms that don't provide enough structure. While this is a valid criticism for those who require more form, it doesn't erase the fact that many children thrive in these non-structured classrooms. Former Montessori students include Steph Curry, Jeff Bezos, and Taylor Swift.

No Curriculum / Tests / Grades

There is no curriculum in the Montessori classroom. The children are the captains of their own ships, essentially creating their own curriculum. This flies in the face of traditional mainstream educational standards that nowadays have teachers teaching to the test.

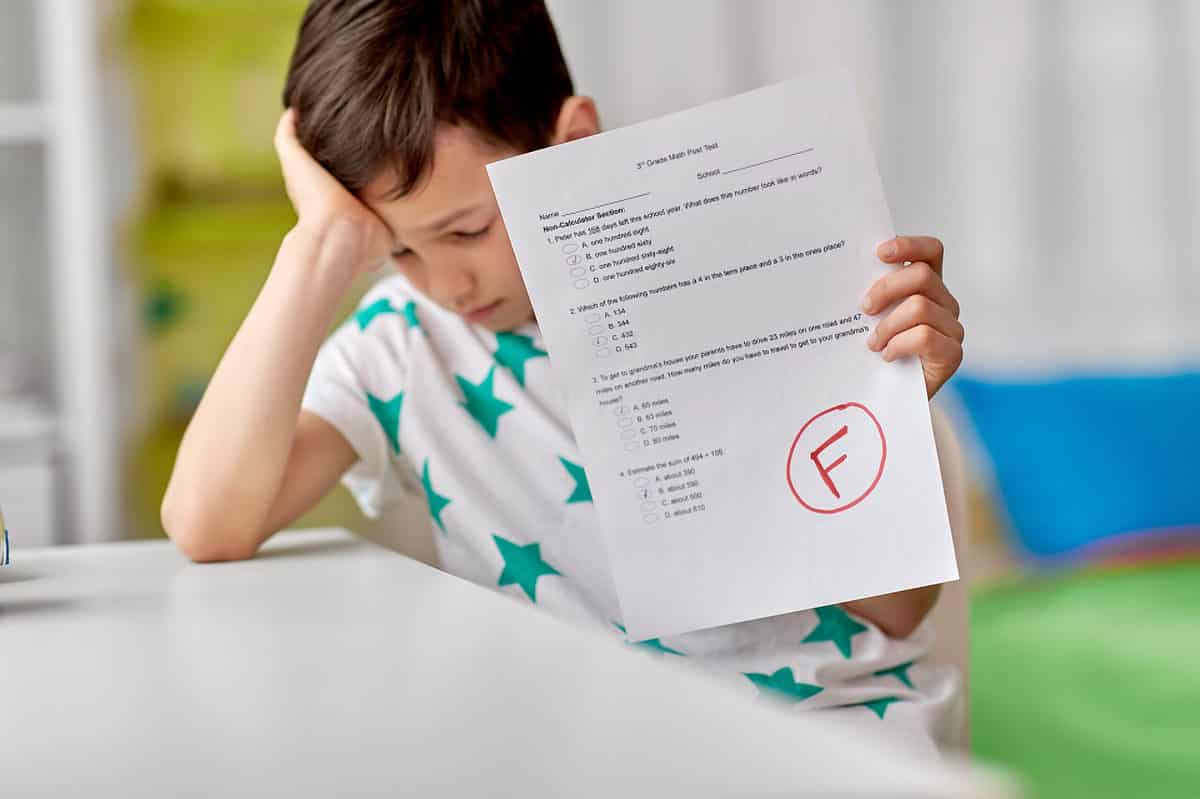

This brings up yet another criticism of Montessori's method. There are no tests or grades given at Montessori schools; no measure of progress beyond the teacher's observations and reports. Montessori was of the opinion that tests and grades result in more harm than good. Students who perform poorly on tests can suffer from low self-esteem, anxiety, and an internalized sense of failure.

©Ground Picture/Shutterstock.com

Performing well on tests, Montessori felt, did not affect a child's abilities or efforts in the long term. Teacher observation and report, though not as objective as formal testing, can offer valuable insights and information regarding students' abilities, quite often providing a more complete picture of the child than a mere letter or number ever could.

Transitioning Out of Montessori

Approximately 150 of the 3,000 Montessori schools in the U.S. serve students through grade 12. Many students, therefore, find themselves transitioning to more conventional schools when they age out of Montessori. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this transition is harder for some students than others.

Montessori proponents believe that Montessori methods prepare students for life beyond the Montessori classroom, arming them with critical thinking skills, self-reliance, problem-solving abilities, and self-discipline.

©ESB Professional/Shutterstock.com

Detractors think that the lack of testing, grading, and homework leaves children ill-prepared and anxious when they encounter them in more traditional schools. While this is undoubtedly the experience of some Montessori graduates, other students who matriculate to more standard schools after attending Montessori reportedly do so with ease.

Are Montessori Schools Bad: Analysis

Are Montessori schools bad? The answer to that question is not black and white. While there is nothing inherently bad about Montessori schools, they are, decidedly, not for everyone.

Accessibility is a valid criticism. Tuition at private Montessori schools is a hurdle that many families aren't able to jump. However, hefty tuition is not limited to Montessori schools. In fact, on average, Montessori schools have lower tuition costs than more traditional private schools. So, in essence, all private schools are inaccessible, making accessibility a general criticism of the private sector, and not a specific criticism of Montessori schools.

Is the lack of structure that is characteristic of the Montessori classroom inherently bad? Experiential, self-guided learning isn't for everyone. But that does not make it bad. Education isn't, nor should it be, a one-size-fits-all proposition.

Children come in all shapes and sizes with different abilities and learning styles. Some children will thrive, unlocking their potential in the Montessori classroom, while others will flounder. That's life.

The absence of a standardized curriculum, traditional testing and grading, and homework seem like a kid's dream and not the nightmare that the critics would have you believe.

We will posit that if the lack of these traditional, presumably objective, measures of a student's abilities and achievements created an obstacle for the majority of students transitioning to conventional schools which employ these means, it would be all over the news and social media.

It's not.

It's not, because the lack of traditional measurements of success and failure does not affect or inform the majority of Montessori students' ability to successfully transition to conventional schools.

Are Montessori schools bad? No. Are Montessori schools a good fit for everyone? No.

Whether or not Montessori is the right fit for your child is best answered by you!

Montessori Criticism in the News

The BBC recently published an article confronting the debate over whether Montessori schools are good or bad. They noted that classroom research is difficult to perform; as such, no significant and reliable study has been performed on the viability of the Montessori education. Instead, most people make their decision on Montessori based on whether its principles appeal to them.

A few studies have been conducted on Montessori schools; one of these studies showed that children who attended a Montessori school tended to perform better in literacy, numeracy, executive function, and social function compared to their non-Montessori peers. BBC noted, however, that this study had a small sample size. As such, its reliability is called into question.

Some researchers have begun attempts to research Montessori's impact on the child, but have been plagued by small sample sizes and an inability to truly randomize their samples. Still, BBC notes, it is a testament to the strengths of a Montessori education that we are still using and discussing it more than 100 years later.

Up Next:

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Joaquin Corbalan P/Shutterstock.com.